Share Magazine Winter 2015

Accessibility and Inclusion at Autism Conferences

20/10/2015

Kabie Brook

It is widely accepted that cars require headlights. These can be seen as an aid, an accommodation, or an adaption to a perfectly useable vehicle to enable use at night. This is needed because our vision is reduced in the dark. Because the majority of people who use cars need this adaptation, it is seen as a necessity rather than a ‘special’ requirement. We need to start looking at society, in general, that way: adaptions that increase accessibility are necessary because if we exclude some we damage the whole.

All events should be accessible and inclusive; an event shouldn’t have to focus on a particular group of people to make an effort not to exclude. Currently, though, even when an event has a focus on autism it is unlikely to get things right for autistic people wanting to attend. Maybe some thought will have been given to accessibility, but because this rarely includes appropriate input from autistic people the result can fall well short of what is required.

Organisers often don’t know what makes an event accessible. Sometimes there is the opinion that if someone is able to travel to the event and wants to attend such an event there’s no need to adapt environments − that this autistic person must be used to living in the ‘real world’. This is just a lack of knowledge about what it’s like to live as a minority in our society. It’s quite reasonable for people not to know, but if those people are working with autistic people or running an event, then they need to do some work to find out.

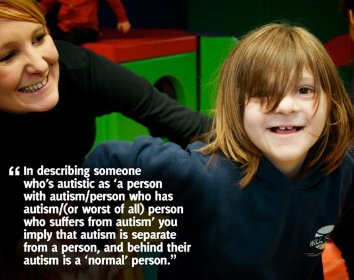

Different autistic people require different things. Just remember that individual requirements will still need to be listened to and accommodated; autistic people don’t just fall out of textbooks and if you only consider us as a list of ‘symptoms’ or ‘traits’ rather than as fully-rounded humans then you’ll get things wrong. But there are some basics that improve access in general.

The first thing to consider is the venue location, choose somewhere easily accessible by public transport, with good parking, away from heavy passing traffic noise and other loud noises (e.g. avoiding flight paths) and make sure to visit, don’t rely on a description from the website. Particular things to consider are natural lighting, ventilation, lingering smells (including kitchen smells), acoustics and decor; it doesn’t need to be bland but avoid anything too fussy. For example, I recently saw an autism conference taking place in a room with a ceiling that resembled a psychedelic light show, pretty to look at but unsuitable as a conference venue.

Ensure that the rooms you book have surplus seating so that people don’t have to squash together and leave plenty of space without seating at the sides and back of the room to allow people to move freely or stand during the event. At autistic-led events the need to move around, perhaps to leave and return is widely recognised, this needs to be accepted at other events too.

If having discussion groups, remember more than one group in a room can make it impossible to follow the discussion and join in; you will need separate rooms. Also provide a separate quiet lunch and break room and a ‘no-queue’ lunch option. You could also offer packed lunches for those people wanting to eat away from the building.

Going somewhere new is stressful, the more prepared we can be the lower the stress and thus the more able we are to attend. Having good quality well-laid out information available in advance reduces stress. This is something that if done well everyone will thank you for.

Include a running order with timings, maps and photos of the building and its location, public transport details, any workshop questions and advance copies of all written material. That sounds a lot when written together but it’s about making materials widely available sooner.

Another idea is to provide details of what food will be available; break times and meal times can be stressful. These are all ways of making the day more predictable that gives a feel of familiarity to an event that if left as an unknown can make it harder to attend.

Minimising noise in large crowds is almost impossible, so it is worth reminding people of this in advance. This ensures that they are prepared and know how to escape the noise when necessary. Quiet areas should be available throughout the day; this includes a space for quiet dining and other breaks. In this space, a ‘no-interaction’ table is useful, a place where people can relax without needing to engage with others. Remind people that attending with earplugs, headphones, ear defenders, dark glasses, stim toys (non-light-up and silent), is welcome.

It’s important to remember that autistic people have been running our own events for decades. The first Autreat was held in 1996, and Autscape, a UK autistic-led conference and retreat, started in 2006. Both of these have been an inspiration for work on creating autistic spaces and have acted as catalysts for autistic community development.

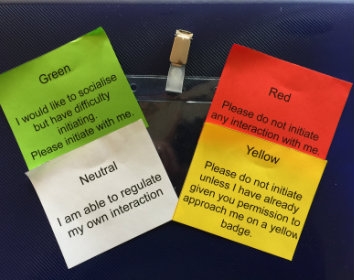

For example, widely used within autistic spaces (and increasingly by others too) are interaction badges. The interaction badge system was developed by and for autistic people (initially for Autreat), but is now widely used at all kinds of conferences and events. The badges allow people to take control of their own interaction in a way that often isn’t possible in our day-to-day lives. Each person who would like to use the badges is given a set of four cards that fit into a plastic wallet: white for ‘I can manage my own interaction’; red for ‘please do not initiate with me’; yellow signals that only people with prior permission can initiate; and green that invites initiation. This provides a solution for those who really want to engage but find it hard to approach people and start the conversation.

Other notable adaptations often seen in autistic community settings include: the waving of hands rather than clapping; requests for attendees to wear low or non-perfumed products and to avoid strong perfume or aftershaves; and instructions not to wear clanking or dangly jewellery that makes a noise. Requests for small changes make a big difference in comfort for many of the attendees.

Including a range of autistic people on planning committees and as paid consultants can help to steer an event in the right direction. Event content should include nonverbal workshops or activities that do not rely upon traditional verbal discussion.

Consider alternative ways to have presentations such as more use of posters, video presentations, artwork and written work. Different ways of hearing people and including their views are also needed.

Including autistic speakers is essential. Many are professionals and experts in their chosen field. We have more to offer than ‘experience talks’ but are often only booked to enact examples of our ‘autisticness’. Our community is a lively and beautiful mix of individuals and this is often not acknowledged.

If you are organising an event, the main questions to ask yourself are: 1) What worth does an autism conference have without including autistic people? 2) Do you see the autistic community solely through a non-autistic lens, and if so, how can you change that?