‘We don’t know what her barriers to learning are - how could we?’ Valuing pupil voice and lived experience as a method to improve inclusion.

Ruth Moyse, Doctoral Researcher, University of Reading

Rosie is fifteen. A bright, articulate and academically able autistic young woman, she aspires to become a large-animal vet and yet Rosie has been unable to attend mainstream education for over a year – a situation she shares with a number of other young autistic woman of school age.

We know today that many autistic girls have been missed from the diagnostic process entirely or have been mis-diagnosedi and it seems that absence from school through quiet non-attendanceii is another way by which autistic girls remain undetected within the system. Whilst the extent to which autistic girls at secondary schools in England are more likely to be recorded as persistent absentees when compared to neurotypical girls or autistic boys is statistically significantiii/iv, the experiences of autistic young women appear historically absent from studies which focus on autism and school exclusion. The scope of my PhD research seeks to make sense of this phenomenon, predominantly by empowering a number of autistic girls to share their experiences within a series of life history interviews. These girls are uniquely placed to identify not just the events and experiences that led to them being out of school, but also to identify meaningful recommendations about how their educational provision could be improvedv. Within my research I was also interested to find out whether any of the schools involved had asked these girls for their views on what they thought would constitute appropriate support whilst they were struggling to attend school.

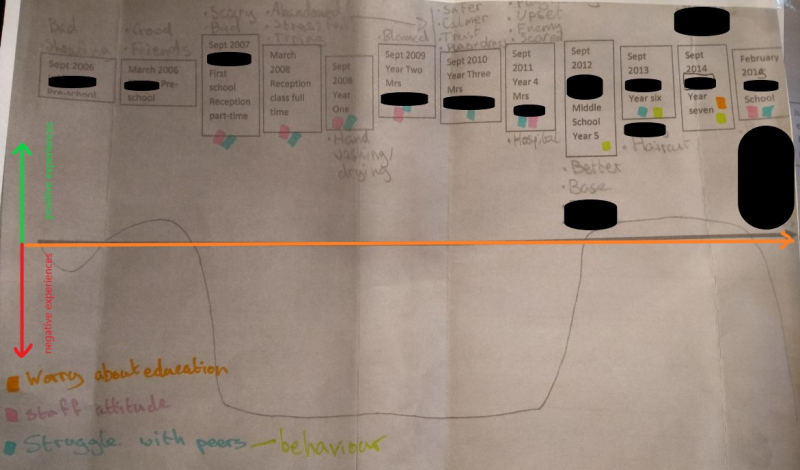

In order to support the voice of the autistic girls that I consulted with, the research also needed to be led by the events and experiences which this group wished to talk about. I was conscious of the potential power imbalances within the researcher-participant relationship and mindful that their journeys out of school were likely to have been traumatic. In order to ensure an ethical process of engagement it was important that each participant felt in control of what was discussed and was able to decide themselves what was significant. To address this, I asked each girl to draw a life chart ahead of our interviews which marked their memories of significant positive and negative events within school. I built questions based on each chart and sent them to the girls before we spoke, giving them the option to remove items they didn’t wish to discuss (no questions were). Interviews were conducted via the Skype text messaging service, in-person at their home or within the University.

What is striking from Rosie’s accounts is that multiple opportunities for schools to understand and respond to her needs appear to have been missed throughout her education. She is now in her seventh placement since pre-school and has been absent from school for about a third of her life (which includes missing two full academic years of education). Rosie attempted suicide at the age of 14.

“It feels like every school I go to, they mess it up for me and refuse to help fix what they’ve messed up.”

A theme of feeling not being listened to, or not being believed appears to run through her story. At the Middle school she attended, chosen for its specialist autism base – Rosie reports her attendance fell significantly from about 60% in Y5 to about 40% in Y7. In addition, even when Rosie was in this school, she was rarely in class; she says that up to 90% of her time was spent in the unit (without work) rather than in lessons. She feels that little to no effort was made to understand why she left so many classes. She explains that she struggled to communicate with staff verbally, remarking that ‘even if I wrote something and signed the bottom of it to say these are my words, no one ever really listened to it.’

Are Rosie’s requirements of a school unreasonable? Her personal construct of her ideal school is somewhere she can do 10 GCSE’s - somewhere that is ‘tidy’, ‘quiet and calm’, with ‘lots of animals around to cuddle’. Adults that ‘know everything they need to know about me and understand me’. A school that ‘wants pupils to achieve their dreams, be happy and feel safe’. She talks of one setting that was ‘really good’ for the first year:

“They didn’t make me try to do things I wasn’t ready for. They let me lead my own progress, so I didn’t feel pressured. I felt safe around the staff because I felt listened to and understood.”

Schools can be challenging places for all individuals and learning is not always easy. However, finding ways to listen earlier to Rosie’s experiences of school may have enabled her to thrive within a mainstream setting and prevented the subsequent toll on her mental health. It is clear from the accounts of these autistic young women that a willingness to understand the stories of girls like her could be good for all pupils.

As Rosie says:

‘Listen.

Listen and believe me.’

REFERENCES

i Gould, J., & Ashton-Smith, J. (2011). Missed diagnosis or misdiagnosis? Girls and women on the autistic spectrum. GAP, 12(1), 34-41.

ii Osler, A. (2006). Excluded girls: interpersonal, institutional and structural violence in schooling. Gender & Education, 18(6), 571-589. doi:10.1080/09540250600980089

iii DfE (2018a, 20.11.18). [Pupil enrolments that are persistent absentees by gender: enrolments with primary Special Educational Need (SEN) of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)].

iv DfE. (2018b). Statistics: Pupil Absence. Retrieved from https:// www.gov.uk/government/collections/statistics-pupil-absence

v Pellicano, L. (2014). Chapter 4. A future made together: new directions in the ethics of autism research. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 14(3), 200-204. doi:10.1111/1471-3802.12070_5